Persistent Attenuation of Lymphocyte Subsets After Mass SARS-CoV-2 Infection

A paper review

To start off, this is the paper to be discussed. Data should be judge on the strength of the methods and the data itself. However, it is always worth to keep a few things in mind.

If there is a breakthrough in our understanding, a new aspect that is surprising, etc, it will generally be published in high impact journals such as NEJM, Lancet, Nature, Cell, Science. If it is a breakthrough, but more specialised to a field, the next tier of journals for immunological findings would be: Immunity, Nature Immunology, Science Immunology, etc. There after the data is solid, makes an important contribution to the field, is an important repeat, or is incremental in what it found. Lastly, there are the predatory and predatory-like journals. Here anything is published, also bad stuff, fake data and just rubbish.

This paper was published in International Journal of Infectious Diseases, which is a society journal. It should be solid, but not a major breakthrough or finding. Then have a look at the authors. In biological journals the more junior people who actually performed the experiments are names first, the senior author (responsible for much of the analysis, providing feedback and direction, leading discussion, obtaining funding and often much of the writing) is named last. The experience of this author and in which field should be found in online profiles such as ORCID. The senior author of this paper can be found here. Again, this is not all determining, but can be informative. The author has had some good work in the journal “Blood” and “Nature communications”, with some additional minor works, and his main expertise is in thrombocytopenia/platelets.

What does the paper show, what does it mean and in which context should we place it?

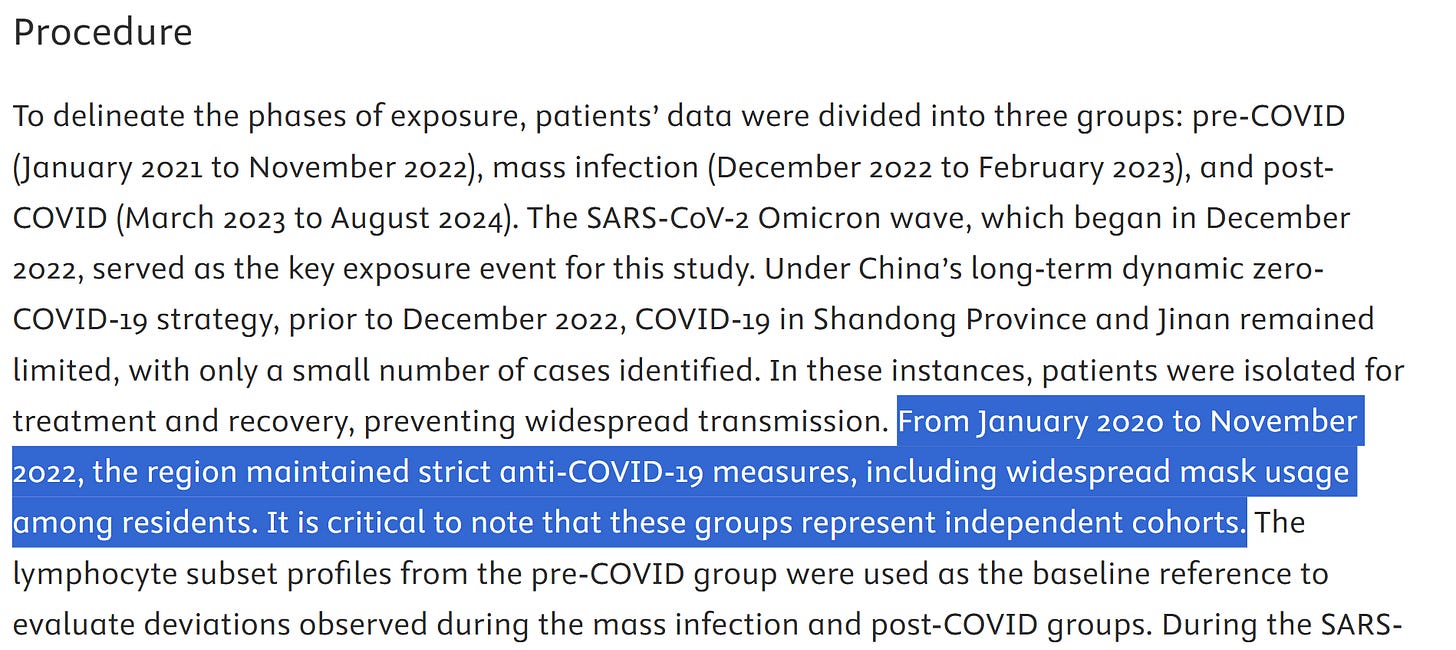

The authors assessed lymphocytes in the blood of three separate cohorts of people in China. There are several pieces of importance. First, China, Shandong Province and Jinan. It can matter where a study is performed due to local circumstances. That is the case here. China has a very strict anti-infection policy after the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 was acknowledged and has spread in Wuhan. This means for a long time the infection rate was low. The authors nicely make use of this. Their pre-COVID cohort are people providing a blood sample between January 2021 to November 2022. This was the pandemic period and people were not excluded or included based on known infection. However, there will likely be few infected cases due to the very strict measures enforced. Of note, other infections such as RSV, Influenza and other respiratory infections will have been much limited as well.

Then measures were relaxed, and the second independent cohort are people infected during December 2022 to February 2023, the omicron wave. Again, infections were not checked, but assumed due to the large scale infections at the time.

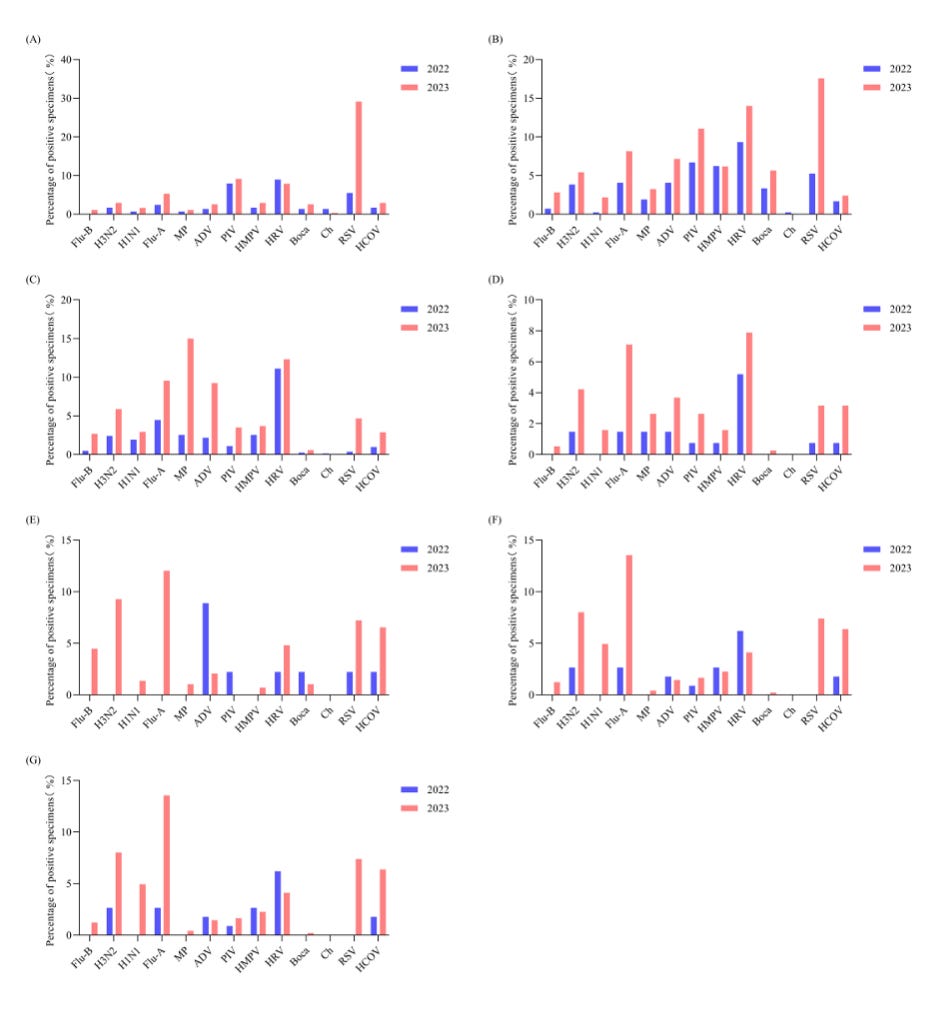

Lastly, there is the post-COVID, March 2023 to August 2024. This is post the initial Omicron wave, and in the absence of strict measures. There is no indication of reinfections, but there are many more infections once the measures were relaxed. This has been reported recently. Please note: these infections and their bounce back is NOT due to SARS-CoV-2 but the population being exposed to the normally circulating infections after a period with limited infection. This, for some pathogens can result in a catch up phase, also referred to as “immune debt”, although I prefer “immune gap” or “infection pause”.

The second important point is that the three cohorts are independent! That means the first cohort, second cohort and third cohort are composed of different people. Although we can plot data longitudinally, to provide a impression, confounding factors can and mostly will, have an impact on this and can cause overinterpretation of the data. In this case, be mindful that the pre-cohort had very little respiratory infection contact, SARS-CoV-2 and others, while the post-Covid cohort was dealing with the resurgence of the usual respiratory infections.

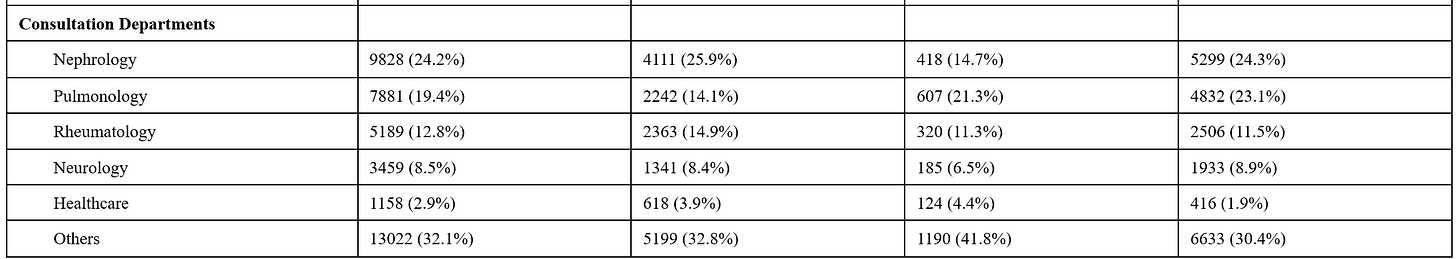

The sample sizes are very good: pre-COVID (n=15,874), mass infection (n=2,844), and post-COVID (n=21,819). But, “the median age was 54 years (38-65), with 52.2% of patients being male, and the highest proportion of patients belonging to the nephrology department, accounting for 24.2%.” The latter is of importance, the blood samples came for people visiting the hospital.

“Baseline lymphocyte subsets were analyzed by age and sex. Age-based stratification (18–40, 41–60, 61–80, >80 years) revealed significant variability in most lymphocyte subsets.“ This is important, the variability in humans is high and changes with age, genetics, and external environmental factors.

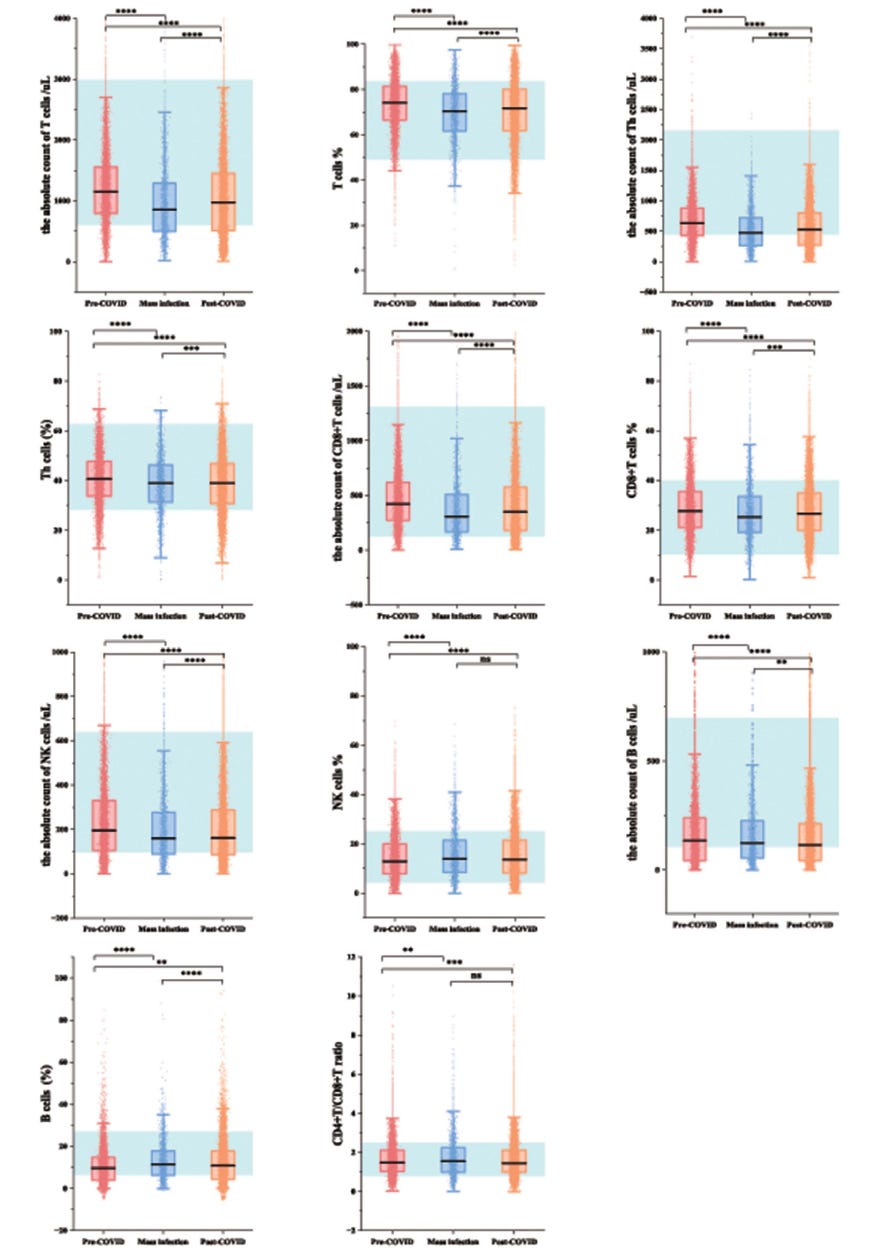

The authors compared lymphocyte subset levels from the mass infection group to those from the pre-COVID group, which served as the baseline. Remember these are different cohorts, and averages are shown. The blue blocks indicate what are considered physiological (normal) values of the white blood cells checked: Total T cells, CD4 (Th) T cells, CD8 T cells, NK cells and B cells.

What we see is that in all groups, the cell numbers in the blood (about 2% of all your lymphocytes) the levels are within what is considered normal. There is no lymphopenia. There are some differences between groups. In some cases there is a mild reduction during the acute infection period. This is normal, cells will migrate to tissues, cytokines may reduce output of new T cells from the thymus, etc. We also see that in the third cohort, post acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, this is restored to levels near what was seen in the pre-COVID cohort.

These cohorts are large and there are significant differences that are annotated. These are pairwise comparisons using the Mann-Whitney U test. With such large numbers of subjects, even very small differences can be significantly different. That does not mean they are meaningfully different with respect to physiology and clinically. We now also need to consider these three cohorts are different people and the confounder of infections being much higher (all respiratory infections) in the post-Covid cohort. If there are several people with other or SARS-CoV-2 reinfections, this can reduce the lymphocyte numbers in the blood a little, but sufficiently to make it significantly different. You cannot and should not make conclusions this is due to the acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. There is no evidence for that.

When more closely looking at the values, this confirms that there is little difference of any concern. The post-Covid cohort is a healthy cohort with good lymphocyte numbers in blood.

The authors write:

“To investigate lymphocyte subsets of the post-COVID group, we compared the levels with the baseline. Post-COVID, the percentage of B cells (10.23% vs 10.34%, P=0.0065), NK cells (13.33% vs 14.05%, P<0.0001), and CD4+/CD8+ T cells ratio (1.43 vs 1.45, P=0.00013) increased, while the percentage of Th cells (40.00% vs 39.41%, P<0.0001), CD8+ T cells (28.29% vs 27.07%, P<0.0001), T cells (73.48% vs 72.37%, P<0.0001), and counts of Th cells (672.43 vs 607.15 cells/µL, P<0.0001), CD8+ T cells (463.23 vs 406.24 cells/µL, P<0.0001), T cells (1227.00 vs 1112.78 cells/µL, P<0.0001), NK cells (217.82 vs 195.00 cells/µL, P<0.0001) were decreased.“

But look closely at the proportions. Percentage are impacted by many factors, such as the increase and decrease of other subsets. If we focus on the numbers, we see that the average differences are very small, nowhere near levels that would cause concern. Again: the infection bounce back will also play a role.

The conclusion “These findings suggest that SARS-CoV-2 exposure may have a long-term impact on the lymphocyte subsets of the population.” I would reject. The data does not show this sufficiently. If there is any difference, it is very small and within physiological values.

The authors then display their findings in a different way . This can be helpful, but does not change the conclusions. I have added a horizontal line to make things a little clearer.

The pre-COVID cohort may be more homogenous due to the much reduces infection level. It would have been nice to see the spread in data there.

My interpretation: Lymphocyte numbers change in the blood, as for every infection, especially a new heavy one such as SARS-CoV-2. It is clear that the numbers bounce back to pre-Covid levels. But, from after January 2023 (Chinese new year?) the variability increases and the readout here may reflect the additional increase in infections reported in 2023.

There is additional data on a specific subset of people with cardiovascular disease. There is limited information about this cohort. The sex and age would be important. How does the pre-Covid cohort compare to the post-Covid cohort with respect to specifics and severity? In addition, the pre- and COVID cohorts are very small.

This makes comparisons and conclusions difficult. It is certainly possible that SARS-CoV-2 infections made CVD symptoms and severity worse and this may be reflected in the blood lymphocyte numbers. This is in agreement with the repeated sampling the authors perform.

Furthermore, numbers in these patients, as the authors also highlight, do recover and differences are not different in the period just after the mass infection, March-July 2023 (samples were pooled), then suddenly drop from August and remain stable on similar level.

There is no explanation for this. The authors mention “T cell exhaustion”, but that will not hold. First of all, there is not T cell exhaustion after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Secondly, there is no chronic infection that may increase the proportion of T cells with “exhaustion” phenotype. Thirdly, this phenotype only applies to SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells, which are a fraction of the total T cells and hence do not explain the large drop. Fourthly, this is equally observed in B and NK cells.

In short, there is no evidence of “a lasting impact on lymphocyte subsets.“ There are suggestions that the pre- and post-Covid cohorts are not similar and the latter is likely undergoing multiple infections compared with the former.

References to T cell “exhaustion” are not relevant or correct, as pointed out above.

Mentioning of “prolonged lymphocyte dysregulation“ also do not hold. Both “exhaustion” and “dysfunction” are not shown.

What the authors do show is the reduction of all lymphocyte subsets assessed in the blood only, they bounce back afterwards. In all three cohorts, the number of lymphocytes remained within physiological levels.

This is in agreement of a lot of studies showing good immunity and immune responses after SARS-CoV-2 infection. There is no “damage”, “dysfuncion” “exhaustion” or “depletion/death/lymphopenia”, SARS-CoV-2 initiates a physiological immune response followed by return to homeostasis.

For references see:

What will population immunity to SARS-CoV-2 look like in a post-vaccine world?

Post-COVID-19 immune competence