Bad science communication: the non-expert getting it very wrong

Some individuals have taken it upon themselves to communicate and interpret scientific research on social media, often without any relevant domain expertise. This phenomenon is widespread across platforms. Their motivations are unclear, but the quality of their commentary is consistently poor. A particularly illustrative case is that of Harry Spoelstra.

Spoelstra is a medical doctor and vascular surgeon; not an immunologist, virologist, or infectious disease expert. His formal training in immunology likely dates back decades to his time in medical school, and he has never authored a scientific paper in the field. Yet, he frequently comments on complex immunological topics as though he were an authority.

Let’s examine two of the papers he has recently cited to support his claims, and unpack why his interpretations are so fundamentally flawed.

The first red flag is the quality of the figures in these studies; they're noticeably poor. The second is the journals in which these papers were published: The Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute and the International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. While a journal’s impact factor or name isn’t everything, these are not high-impact publications. One is a national journal with limited international reach, and the other is a niche specialist outlet.

These issues don’t automatically invalidate a study’s findings, but they do raise questions about the rigour of peer review and the broader relevance of the research. And when those papers are used to make sweeping claims about complex viral immunology by someone without relevant expertise, the need for scrutiny becomes all the more urgent.

“Co-infections and Reactivation of some Herpesviruses (HHV) and Measles Virus (MeV) in Egyptian Cancer Patients infected with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)“

In classic scaremongering style, Spoelstra finds this terribly worrying

.

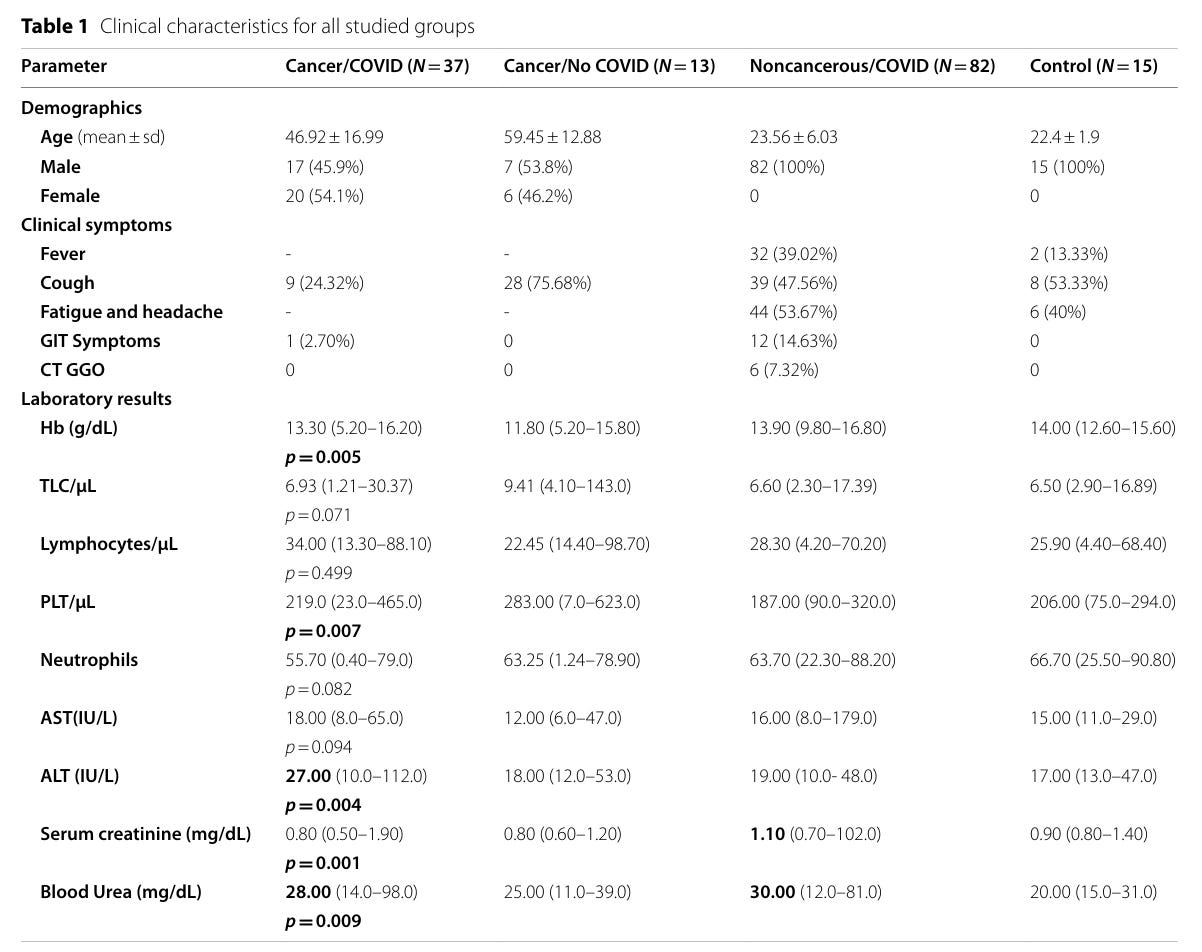

The study compares patients with and without cancer, and with or without SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, the study groups differ significantly in key demographic characteristics, most notably, age and gender. The cancer group is considerably older, and all controls are male, introducing substantial confounding variables that are not adequately addressed.

Importantly, the data show that lymphocyte counts are high in both SARS-CoV-2–infected groups, contradicting the claim of lymphopenia associated with the virus. This finding alone undermines the narrative of broad immune depletion. Other statistically significant differences are reported, but the poor study design, lack of matching, and uncontrolled confounders severely limit the interpretability of these results.

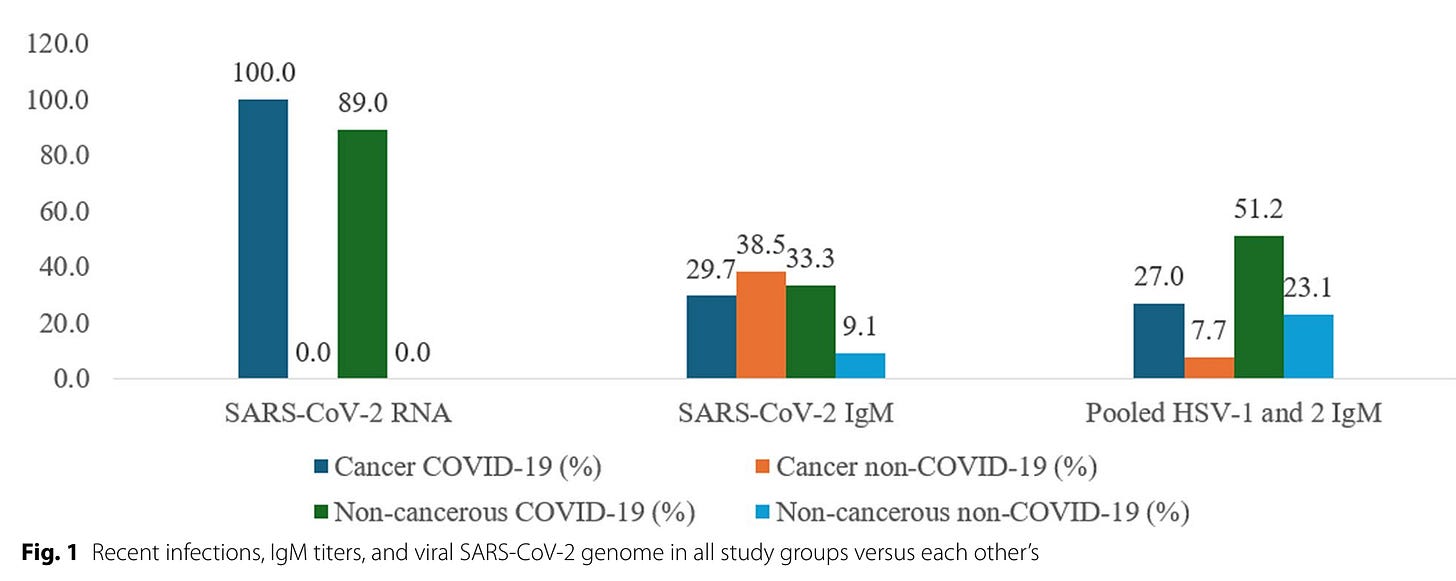

Patients were recruited between September 2020 and September 2022. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed using qRT-PCR; widely regarded as the gold standard for detecting active viral presence. However, in a methodological pivot, the authors then rely on ELISA to measure antibody responses. Specifically, they focus on IgM antibodies, which are low-affinity antibodies typically produced early in the course of an infection. The detection of IgM against SARS-CoV-2, as well as against HSV-1 and HSV-2, is reported across different patient groups.

Critically, the presence of IgM does not equate to current viral infection. It simply indicates that an immune response was mounted at some point in time—possibly weeks months or years earlier. The detection of HSV-related IgM, in particular, does not imply active herpesvirus replication or reactivation, yet the authors make no such distinction. This conflation of immunological memory with active infection misrepresents the data and contributes to misleading interpretations.

IgG antibodies are typically produced after IgM during an immune response and persist longer, serving as markers of past exposure or vaccination. In this study, it must be assumed—though never stated—that the detection of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG refers to antibodies against the Spike protein, the target of all currently approved vaccines. It is also reasonable to infer that most, if not all, participants had been vaccinated by the time of serum collection, particularly given the recruitment period spanned 2020 to 2022. Yet the paper inexplicably omits any mention of vaccination status, a critical variable when interpreting anti-Spike IgG data.

Even more problematic is the presentation of the data: values on the Y-axis of the figures represent the percentage of subjects testing positive in the ELISA, not quantitative antibody titres or concentrations. This makes the figures fundamentally unsuitable for drawing conclusions about antibody levels, magnitude of immune response, or durability of immunity. It reduces the serological analysis to a crude binary metric, while pretending to offer immunological depth, an oversight that borders on misleading.

It’s well established that most people will have encountered common viruses like HSV-1, HSV-2, EBV, and measles during their lifetime. Strikingly, in this study, none of the non-cancer, non–COVID-19 control group showed seropositivity for HSV-1 or HSV-2. This is highly implausible. Numerous seroepidemiological studies have demonstrated widespread prevalence of herpesviruses in adult populations globally, particularly HSV-1, which can exceed 70% seroprevalence depending on region and age group. Such an absence raises immediate concerns about either sample selection bias or technical flaws in the ELISA testing.

Looking at EBV and measles IgG, the data suggest similar profiles between groups, with one interesting pattern: the younger groups show lower measles IgG positivity compared to the older cohorts. This may reflect the introduction of the MMR vaccine (which includes measles) in younger generations, while older individuals may have been infected or missed immunisation campaigns; an interpretation that is biologically and epidemiologically sound.

However, the authors then take a dramatic leap into scientific error, a leap that is uncritically echoed by Harry Spoelstra. They claim that elevated antibody levels—specifically against measles—reflect viral reactivation. This assertion is categorically false. Measles virus is not a latent virus; it does not persist in a reactivatable form like herpesviruses or retroviruses. Once cleared, the virus is gone, and long-lasting immunity is mediated by memory cells and antibodies, not latent reservoirs.

To credibly claim viral reactivation of any virus—be it herpesvirus or otherwise—direct evidence of active viral replication is needed, typically through quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect viral DNA or RNA. No such testing was done here. Instead, the authors base sweeping claims on crude antibody presence or variation in IgG seropositivity percentages. This is not just methodologically unsound, it misrepresents fundamental immunology. Elevated or declining antibodies from past infections are common and reflect individual variation, not active infection or immune system dysfunction.

The observed differences in antibody patterns are most pronounced in the cancer patient groups, which is entirely plausible. Cancer, along with associated treatments such as chemotherapy, is known to weaken immune surveillance. In such contexts, herpesvirus reactivation is well-documented, as these viruses are capable of establishing latency and re-emerging under immunosuppressive or stressful conditions. The same is true for acute infections like SARS-CoV-2, which has been shown in some studies to trigger reactivation of latent herpesviruses like EBV or HSV.

But then the authors, and unfortunately, Harry Spoelstra as well, take a wild detour into pseudoscience by trying to link these changes to measles virus reactivation. This is not just wrong; it's scientifically ludicrous. Measles is not a virus that establishes latency. Once cleared by the immune system, it does not persist. There is no mechanism or precedent by which measles virus “reactivates” later in life, under stress or otherwise. The immune memory response to measles involves durable IgG antibodies and T cells, not ongoing viral replication or latency.

To top it off, the paper launches into a meandering “discussion” filled with speculative and unsubstantiated claims. One standout example is the assertion that “computational homology modeling suggests the MMR vaccine could provide broad neutralising antibodies against numerous diseases, including COVID-19.” This is pure fantasy masquerading as science. There is no credible evidence, computational or otherwise, that MMR vaccination confers any functional neutralising immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Homology in protein sequences does not equate to cross-protective immunity, and this notion has been thoroughly debunked in the scientific literature.

In short, what the authors present is a mix of immunological confusion, flawed interpretation, and unjustified extrapolation, and the fact that it is being uncritically amplified by individuals without virology or immunology expertise, like Spoelstra, only magnifies the misinformation.

What about the second paper?

Increased Incidence of Intracranial Complications Following Pediatric Sinogenic and Otogenic Infections in the Post-COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Of course, Harry Spoelstra finds this deeply alarming, because what would a social media medical influencer be without a little manufactured outrage to drive clicks and shares? His chosen evidence this time? “Both acute and chronic sinusitis are diseases that affect most people at some point in time. Typically, this disorder is classified depending on the time criterion: acute sinusitis lasting up to 4 weeks, subacute type 4–12 weeks, and chronic infection lasting longer than 12 weeks. Bacterial and fungal etiology most frequently lead to neurological complications in the form of suppurative disease and non-suppurative complications.” The world did not discover sinus infections or rare complications with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. Bacterial and fungal etiologies have long been associated with severe complications like subdural empyemas and cerebral abscesses. These are rare but well-documented and have existed long before the pandemic.

Children routinely contract respiratory viruses. Their infections are often milder than those in adults, a benign course in children, but they are not without risk. Complications such as sinusitis occur in an estimated 5–10% of cases. This is not a SARS-CoV-2-specific phenomenon, it’s the nature of pediatric respiratory illness.

Extradural empyema, subdural empyema, and cerebral abscess are documented complications of sinusitis and otitis. These are long-standing features of paediatric ENT complications. They do not require a novel coronavirus to occur, and their incidence has never warranted public panic. Spoelstra elevates their existence into a pseudo-epidemic without context or data.

Influenza, RSV, adenovirus, or other viruses can indirectly complicate sinus drainage or provide opportunity for bacterial or fungal coinfections. But Spoelstra’s implication that SARS-CoV-2 uniquely and dramatically increases risk is unsupported by current epidemiological evidence. A transient increase in risk does not equal a major public health crisis.

Because engagement thrives on fear. And when fear is dressed up as "concerned clinical insight", particularly from someone with no training in immunology or infectious disease—lay readers are more likely to believe there is a new, unchecked threat on the horizon. But this isn't evidence-based medicine; it's algorithmic panic.

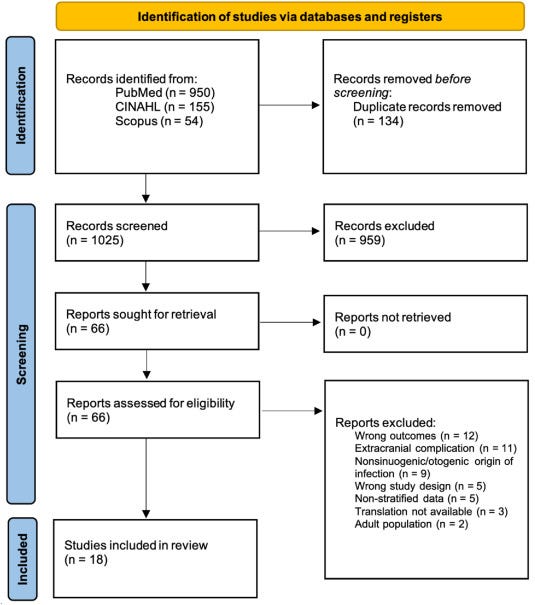

This is a meta-analysis “A literature search was performed using the PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL“. That sounds promising at first glance. These are credible databases. However, the strength of a meta-analysis lives or dies by its inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the quality of the underlying studies. In this case, the authors report that they found a substantial number of studies, yet ultimately included only 18.

The authors set out to determine whether there were more paediatric intracranial complications during the COVID-19 pandemic than before. To do this, they reviewed English-language articles on the topic. But here’s the first problem: publication volume alone is not a proxy for disease incidence. We were in a publishing boom. COVID-19 became one of the most heavily covered topics in biomedical literature, and anything adjacent to it, like rare complications, has naturally attracted attention. This is a textbook case of reporting bias. If more papers are published on a topic in recent years, one might mistakenly infer an actual increase in disease burden when all that’s changed is academic interest and reporting frequency.

If the goal was to determine whether SARS-CoV-2 infection increases the risk of paediatric intracranial complications, the correct approach would be a case-control or cohort study comparing children with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection within the same timeframe. But the authors didn’t do that. They admit:

“Confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis data were collected when available; however, the data were too sparse and heterogeneous across studies to allow for stratification in the analysis.”

Despite this, they go on to draw conclusions that imply a causal link between COVID-19 and increased intracranial complications. This is a serious methodological flaw.

Another critical point: these complications are not specific to SARS-CoV-2. In fact, many are caused by bacteria and fungi. According to CDC data, there was indeed a noted increase in streptococcal intracranial empyema and abscesses during 2021–2022—but this was interpreted as part of seasonal variation, with incidence already declining in the latter half of 2022.

When interpreting findings from this meta-analysis, context is essential. The 18 included studies vary:

Some show no difference in intracranial complication rates before and after March 2020.

Some report a reduction.

Some show an increase

most are attributable to bacterial or fungal causes.

Across the board, case numbers remain low, and SARS-CoV-2 infection status is often unknown or unconfirmed. In other words: the data do not support a strong causal role for SARS-CoV-2.

Paediatric intracranial complications deserve medical attention, but the evidence does not support the idea that COVID-19 has made them dramatically more frequent or dangerous. Reactions like Spoelstra’s reflect a broader trend of misinterpreting data, ignoring study limitations, and overstating risk, all while lacking the virological or immunological expertise needed to properly assess these studies.

Below is a breakdown of all 18 studies. The direct cause is mainly bacterial of fungal, and incidence is low. The role of SARS-CoV-2 is not directly assessed and frequently the infection status, whether acute or past, is unknown.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Marc’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.